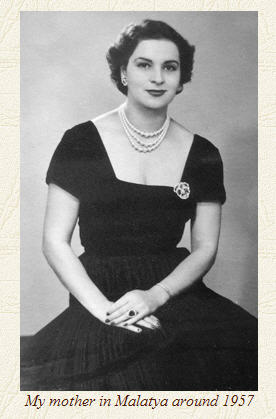

The Author's Family

|

A Love Story Lent a Helping Hand by Kemal Atatürk Tribute to General Kemal Atalay by Bulent I. Atalay

|

June 23, 2006, the cruise ship, Crystal Serenity, on which I am serving as a special topics lecturer, docks in Thessalonica, Greece’s second largest city. At the turn of the 20th century, as “Selanik,” it was the Ottoman Empire’s second largest city. The streets of the ancient city are poorly laid out; there is no grid with a north-south and east-west bearing. Like most old cities, it has evolved according to the natural topography of the land, with a citadel perched on its acropolis. Worse yet all the signs are in Greek, and although, as a physicist, I know the Greek alphabet and can sound out the words, I have no idea of their meaning.

My wife, Carol Jean, and I, along with two friends from the Serenity, Stephen and Linda Young, are in search of Atatürk’s birthplace, located next to the Turkish Consulate. To get our bearings, we drive up to the acropolis of Thessalonica, where the ancient Byzantine walls still stand, restored; but with time running out to return to the ship, we are nearing a frenzied state. Quite suddenly we happen upon a young boy, an apprentice to an automobile mechanic, who senses our frustration, and in lucid English, asks if he can help us. When we tell him the address, he responds that he does not know the place himself. But then he strolls over to his boss. They discuss our plight. When he returns, he tells us that they will lead us in their own pickup truck.

The distance turns out to be no more than a mile through serpentine streets, but it takes twenty-minutes to negotiate the distance through the virtually impenetrable rush-hour traffic. Then as Stephen shoehorns the rental car into a tight spot, I jump out and begin a mad jog up the street, in search of Number 17. Midway up the next block, perhaps a hundred yards away, is the two story frame house that I have seen in old faded pictures, the upper story cantilevered over the lower, evocative of the 19th century houses one sees in Istanbul. Atatürk’s house at last, 17 Apostolou Pavlou! And the narrow street, where my grandfather, Ismail Hakki, as a young boy, played with Mustafa Kemal, his closest childhood friend, who would go on to rescue Turkey, then set on a seemingly inexorable course to disintegration. A grateful parliament of the republic he created would later bestow on him the appellation, Atatürk, “Father of the Turks,” then proceed to retire the title permanently, lest someone else try to adopt it.

Later that afternoon the Serenity sails east, on a course south of the Athos Peninsula, with its splendid monasteries. Early in the morning the following day the ship slows down to allow a pilot to board and guide us up the Dardanelles. I stand on the top deck, surveying the magical panorama. Sailing up the 46-mile straits, it is impossible not to be moved by the spirit of these hallowed lands, witness to spectacular drama. On the starboard side, and not more than a few miles away, lie the ruins of Troy, the legendary city destroyed in the mid-13th century BC by the Mycenaean Greeks. Almost eight hundred years later the Persian King Xerxes lashed his ships together, creating a pontoon bridge, and crossed the Dardanelles on his way to invading Greece. And another hundred years later still Alexander the Great repaid the favor, constructed his own pontoon bridge, and crossed over to Asia, taking the first step in his relentless bid to conquer the world. Six hundred years ago the Ottomans began their isolation of Constantinople by stretching chains across the straits. Finally, a mere one hundred and seventy years ago at the same spot the Romantic poet Lord Byron, an exceptionally strong swimmer, crossed the Dardanelles, known for its treacherous currents. Consumed with classical Greece and its fertile mythology, Byron was reenacting one of Leander’s nocturnal crossings, in order to visit his lover, Hero, living on the other side.

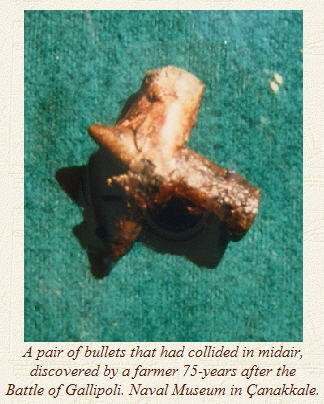

THE ANZACS

The Serenity enters the Dardanelles and sails in a northwesterly direction. Prominently visible near the the tip of the Peninsula are the monuments of the Turks, the French, and the British, each honoring an unknown soldier lost in the Gallipoli Campaign. The Australian and New Zealand monuments are tucked away on the western shore of the peninsula and cannot be seen from the straits. The land is literally pockmarked with numberless trenches. It is on this sliver of land that hundreds of thousands of troops — Turkish and Allied — faced each other in 1915. Australian and New Zealand troops, mobilized into the "Australian and New Zealand Army Corps," or "ANZAC." When it was all over, a half million young soldiers, approximately evenly divided between the two sides, had been wounded or killed. The smoke of battle — bullets and cannon shells — turned the sky opaque at midday. Perhaps because of the shared misery, the two sides came to respect each other to the point where, it is said, a daily coffee and smoke break would take place, allowing the soldiers to climb out of their bunkers in relative safety. But when they returned, if as much as a hand showed, it would be shot off. No doubt, this was rare. Indeed, another story has it that Turkish soldiers soldiers threw small boxes of hand-rolled cigarettes from their trenches to the soldiers occupying enemy trenches. The ANZAC soldiers would throw tins of their food in exchange. The Turks would open and taste the canned food, then throw them back. Note: When individual lives are concerned, it is never fair to round off numbers. Accordingly, it behooves us to present the most detailed figures available: Turkey sustained 164,617 wounded and 86, 692 killed. The allies — Australia, Britain, France, India, Canada and New Zealand — saw 96,937 wounded and 44,092 killed. (These are figures from the Australian War Memorial.)

The brilliant pioneer in atomic physics, Henry Moseley, was here. Having performed ground breaking research in x-ray spectroscopy, he resigned his research position at Oxford University to volunteer fighting for the Crown. Then in August of 1915, still 27 years old, he was killed in action. Here also was another Oxford man, Rupert Brooke, poet. Having romanticized warfare in his earlier poetry, he died not in battle, but on the way to battle, of sunstroke just two days before the Battleship Hood delivered the troops to the area. “Rupert Brooke is dead… [his] life has closed at the moment when it seemed to have reached its springtime," wrote Winston Spencer Churchill in his obituary for the young poet. And indeed, Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, who had originally masterminded the scheme — to sail up the Dardanelles, take control of Istanbul, and then strike at Germany from its “soft underbelly.” The failed campaign led to Churchill losing his job. On the facing hills on the portside, one sees a flat white figure — an image created in limestone of a soldier clutching his rifle with one hand, signaling his comrades to follow him into battle with the other. Next to it, spelled out in limestone markers, “Halt, Traveler. This ground on which you unwittingly tread marks the spot where an era came to an end."

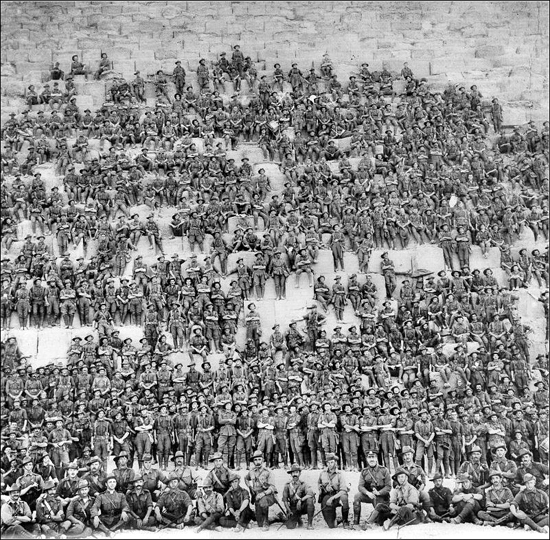

Left: Alec Campbell (1899-2002), the longest living Anzac and the longest living veteran of Gallipoli. Having enlisted at age 16, he lived to be 103. Right: A group portrait of the Australian 11th (Western Australia) Battalian, 3rd Infantry Brigade posing in front of the Great Pyramid of Gizeh. The dramatic photograph, dated 10 January 1915, shows several hundred troops during a break from their training in Egypt. The battalian, among the first to land at ANZAC Cove on the Western shores of the Gallipoli Peninsula, suffered 378 casualties, or one-third of its strength. (My gratitude to Cem Ozmeral for making the photo available.).

ATATURK'S LETTER TO THE MOTHERS OF THE FALLEN AUSTRALIANS

And then one also remembers the deeply comforting, profoundly generous words with which Ataturk addressed the families of the fallen Aussies and Kiwis:

"Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives... you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours... You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well." — Kemal Atatürk

Atatürk’s poignant message is inscribed in the Turkish Memorial to the Unknown Soldier in Gallipoli, and inscribed also at the Atatürk Memorials in Canberra, Australia and Wellington, New Zealand. It is no wonder that in distant Australia and New Zealand, there is still a sense of kinship for Atatürk and the Turks — enemies, but fellow witnesses to the unspeakable horrors of trench warfare — and, conversely, a resentment of the British politicians who sent a generation of their young men to fight and die in a land half-a-world away. For the Turks, the Australians, and the New Zealanders Gallipoli would forever be regarded as the moment when they gained their national identities.

An integral part of Anzac Day Services in Australia and New Zealand during the past nine decades has been a reading of the third and fourth verses from For the Fallen, composed by the Oxford educated Laurence Binyon (1869-1943)

I was introduced to the last verse when the Right Hon. Mike Moore, the Ambassador and former Prime Minister of New Zealand, read it at the Anzac Day Service at the National Cathedral, Washington, DC on 26 April 2011.

Through the generations, my family has demonstrated an almost idolatrous admiration and affection for Atatürk. His pictures abounded in my parents’ home in Istanbul, although only in one picture is my father, then a young second lieutenant, seen with Atatürk himself. Certainly a unique, iconic national hero, he made a small, but critical contribution to my family. He served as catalyst in the marriage of my own mother and father.

THE DRIVE DOWN THE PENINSULA

I have been through the straits, as well as on both storied shores many times, but the visit just the day after seeing Atatürk’s birthplace in Thessalonica makes the experience of sailing the straits on this occasion utterly unforgettable. I remember a visit in 1967, when Carol Jean and I, accompanied by my mother and father, drove down the Gallipoli Peninsula from Istanbul. My father, General Kemal Atalay, the Undersecretary of Defense, had taken his annual holiday so that he could be with us. I was visiting my parents with my wife and two very young children. Just three years earlier on a visit to Washington, DC my father had seen our daughter, Jeannine, then not quite a year old and just beginning to walk. This time in Turkey he would meet our son, Michael Kemal Atalay, who had just turned one and was beginning to walk. But on this excursion to Canakkale, we left the children with my grandmother at the army resort in Fenerbahce, Istanbul, which we were using as home base. And it was on our lengthy drive down the Gallipoli Peninsula that my father first told us the story of his father, Ismail Hakki, and the family’s “Atatürk connection,” how he and my mother met, and the circumstances of their marriage.

My grandfather fought in those trenches for eight months, through the better part of 1915. A photograph was taken of his company during a break in the action. Immediately after the cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of the ANZACS, he briefly traveled to Edirne (Roman Adrionople) on assignment, and while there, on January 1, 1916, had a photograph taken of himself. He inscribed on the back of the photograph in old Turkish (right-to-left), “Sevgili Teyze" ("Dear aunt"), I have survived eight months of action in Gallipoli. I will soon leave for the Eastern Front, there to face the Arabs and their recalcitrant English leader.”

Group portrait of my grandfather's company during the Gallipoli Campaign (1915). He is seen standing in the rear row and approximately two-thirds of the way from the left (an oblique dark line identifies him). Atatürk is seen at the intersection of the diagonals, the center of the picture, wearing a dark fez and a uniform with a white collar. If the diagonal line identifying Ismail Hakki is extended, it would pass through the figure of Atatürk. The original of this photograph hangs in the Naval Museum in Çanakkale.

Just before leaving for the Eastern Front, he visited the small town of Biga, lying to the east of Çanakkale and Troy. He went to see his young family, ensconced in the town since

shortly before the war began. There were his wife, Münire Hanim, and three young children, the oldest, a daughter Muazzez; the middle, a son Muammer; and the youngest, my father, “Mustafa Kemal”— named after Ismail Hakki’s childhood friend, and in accord with his wishes. (Last names were not introduced into Turkey until 1934. It can make genealogical research a hopelessly difficult task.)

After only a day or two with his family, however, Ismail Hakki had to leave again, this time to fight on the Eastern Front. There he would die, fighting against the Arabs and their “recalcitrant” English leader, T. E. Lawrence, who would become known as Lawrence of Arabia. My grandfather’s body would presumably be interred somewhere in southeastern Turkey. According to the tradition prevailing in the family, Atatürk had his aide-de-camp carry my grandfather’s handgun and sword back to Biga and presented to my grandmother, along with Atatürk’s promise that after the war he would find the family and see to their needs. But even before the war ended, my grandmother and her children moved to Istanbul, where they could get help from close relatives.

ALIN YAZISI (FOREHEAD INSCRIPTION)

Growing up in Kadiköy on the Asian side of the Bosporus, my father and his older brother, Muammer, both aspired to make their careers in the military, following in the footsteps of their late father. Just a few weeks apart they reported to the military recruiting office, had their interviews, took the military college’s entrance examination, and they both passed. My father presented some dubious documentation showing him to be two years older than he actually was. When they underwent physical examinations, my uncle passed with flying colors; my father, however, was told that he suffered from a heart murmur and could not be admitted. His hopes dashed, he staggered around dejected, tears streaming down his cheeks. After wandering listlessly for some time, he found himself at a ferry dock. The ferry was just pulling away from the dock. My father used to say, any other time, he would have just jumped onto the ferry, as he had done numerous times before, but that day it was not be — it was not “written on his forehead!” That day it was not his fate to take the ferry and go home. He was a lifelong believer in fate – “If it is written on your forehead, it will come to pass,” he would always say. He sat on a bench on the pier, utterly disheartened. Then suddenly an elderly gentleman appeared, and sensing my father’s despair, stopped and queried, “What is the matter, son?”

My father answered that he had always hoped to become an officer, but he was denied admission to the academy. The man appeared genuinely sympathetic. Attempting to console my father, he remarked, “There are so many different professions, and a good looking, clean cut young man like you should be able to become or do anything you set your mind to. You could become a doctor, an architect, or even a diplomat. You have a distinguished demeanor.” My father, his voice breaking, responded, “My greatest wish in the world was to become a soldier, just as my father had been.” Without raising his eyes from the ground, he continued, “But I’ve just been told that I am suffering from a heart murmur that will keep me out of the academy.” He still had the x-ray film in a folder tucked under his arm, which the older man suddenly noticed. At this point, the man revealed to my father that he was doctor — a professor at the medical school. “May I see the film,” he asked. Then removing the film from its sleeve, he held it up to the sunlight, and studied it for a full minute, squinting, scanning. Then, with a smile, he told my father, “Let’s go together to the hospital.”

When they got to the hospital a medical board was in session. That did not stop the old man. He barged into the room, my father right behind him. Again, he removed the film from the sleeve and held it in front of a light box. “Gentleman,” he announced, “…you have made the same mistake again. There is nothing wrong with this young man’s heart.” He went on to explain their misdiagnosis. To make his point, he placed his stethoscope on my father’s chest and listened for the characteristic sounds of a heart murmur. “There is no swishing or whistling, beyond the normal ‘Lub-Dub’ sound.” He reiterated, “Classic misdiagnosis!” It turned out that this remarkably kind man was in reality one of the most senior physicians on the medical school faculty and a one-time instructor to most of the other physicians in the room.

The peaks and valleys of that day’s emotional roller coaster ride — missing the ferry, meeting the professor of medicine, having the faulty diagnosis corrected, and being admitted into the military college — “were all written on his forehead!” Thereafter, my father would always have an abiding admiration for physicians, and especially for those in cardiology. He lived into his nineties, and he spoke with bursting pride of his grandson, Michael Kemal Atalay, who would earn combined MD/PhD degrees at Johns Hopkins in cardiac imaging, in advent of doing medical internship at Harvard as “Dr. Dr. Atalay.”

Built in 1845 on the Asian Shore of the Bosporus, the military college, Kuleli, is an unusually prepossessing building that derives its name from the two prominent flanking towers (Figure 4).

The years at the academy were successful for both brothers. They enjoyed their time, they studied hard, and they made lifelong friends. Many would also accompany them in their rise through the military ranks. Both brothers were successful athletes, starters on the school’s soccer team, my father as left wing, his brother as the high-scoring center forward. Father would often speak of his brother, about his extraordinary prowess on the soccer field. But in academics it was my father who would excel and leave a mark. He graduated in the class of 1930. Not long afterwards, at an engagement party for his close friend, Nüzhet Bulca, he would meet the guest of honor, none other than Kemal Atatürk, the beloved President.

As my father recalled the memories of that day thirty years ago, Carol Jean and I remained transfixed. My mother, who must have known the story all along, was just happy that we were hearing about it. But then I interrupted, asking rhetorically, "You told him then that you and your brother were the sons of his oldest friend, Ismail Hakki?” “No, I couldn’t…” he said, “I didn’t want any favoritism. If Ataturk had found out who I was, he might have taken me as an aide, and I would never have been able to prove myself.” (He was modest. He was shy.)

A few years later he would take the examinations that would gain him acceptance into the Army War College and the status of Kurmay. He could now realistically aspire to attain the highest ranks in the army.

THE KÖKDEMIR FAMILY EDIT THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH

My maternal grandfather, Bahaddin Faik Kökdemir, was born in 1892 in Gerze, a town in the province of Sinop on the Black Sea. He attended primary and middle school in Kastamonu, also in Sinop. Subsequently, relocating to Istanbul, he attended high school, followed by Harbiye, the Military Medical School, located on the southern entrance to the Bosporus. In 1914, the year that WWI broke out, he received his medical degree along with a commission as a captain in the army. Shortly after graduation in 1915, he married my grandmother, Refika. They had three children — the first child, a son named, Ertugrul Pertev, was born in 1916; their second child, my mother, Nigar Esma Atalay, would be born three years later; the third child, Hüsrev, would come almost a generation later,

in 1938. (My grandfather had, however, been married once before, but that marriage had ended in divorce. From that marriage he had also a son and a daughter.) The family posed for a portrait in Istanbul (ca 1921), my uncle approximately five years old, my mother just two. My grandfather is seen wearing the customary fez, my grandmother a scarf over her head.

Then in 1926 when my grandfather was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship to undertake postgraduate work in medicine at Harvard, he would journey to the United States with his family, and spend the next three years on the East Coast of America. After a year at Harvard, he was given an extension of his fellowship and allowed to transfer to Johns Hopkins Medical Center, ostensibly to receive additional training at America’s other great medical institution. Accordingly, the family moved to Baltimore for the next two years. In 1929, with my mother and uncle — ten and thirteen years old, respectively — my grandparents returned to Turkey and settled in Ankara. The children had learned to speak flawless English, a skill that would serve them well the rest of their lives. Shortly after they returned to Turkey with some newly acquired western social habits — they found that Turkey was amidst some of Atatürk’s social reforms, launched during their absence. Western style clothing was in, the traditional Middle Eastern garb — fez, turban, veil — was out; the Ottoman-Arabic script, written from right-to-left, was being replaced by the Roman alphabet, written from left-to-right — reforms that my grandparents welcomed, reforms that would make their own adjustment in returning to Turkey so very much easier.

In Ankara my grandfather was to become a successful physician, an internist,

as well as a specialist in public hygiene. As a physician he was well known to administer to rich and poor alike, but especially the poor! As a child I remember occasions when patients would pay him with a pot of yogurt, a live chicken from their chicken coop, or not at all. And as a public hygienist with a pair of books that he had published on the subject and in the late 30s he would serve as a member of parliament, a mebbus, after being nominated by Dr. Refik Saydam, the celebrated Minister of Public Health. But disillusioned by politics and politicians after just one term in office, he returned to his medical practice.

When my parents first met, my mother was only seventeen years old, my father 26. She was a student in a local school, and my father, a young officer on temporary assignment, teaching military science at a nearby high school. It was not long before they became enamored with each other, but maintained a proper distance. Much, much later my father would confess to me, rather sheepishly, that they had once met secretly, having arranged to meet in front of the movie theater in the downtown square, Ulus Meydani. There they would see a film together, come out of the theater, still maintaining the most proper decorum, and then bid good-bye. But they would not forget each other.

One day a few months later, my father, uncommonly bashful, made an unusually brazen move. He telephoned my grandfather, the physician, and arranged for a private visit – not seeking any professional service. He was there to ask for my mother’s hand in marriage. He explained to my grandfather that his own father had died in WWI, that he himself was a military officer who received a modest, but dependable salary, but that each month he faithfully gave a portion of his salary to his widowed mother.

My grandfather was impressed by the personal visit —

untraditional in that no go-betweens were involved. He had seen during his years in America that intermediaries were not involved in asking for a girl’s hand. But about giving his blessings to the marriage, he admitted his reticence, “I don’t want my only daughter to be married to a soldier who might get killed one of these days, and leave her a widow. I must take this under advisement. I will get back to you.” Then after a pause, he continued, “Please, call us in a month.” He even gave a date for my father to call again.

In discussing the dilemma with my grandmother, there was agreement: he was very polite, he was deeply devoted to his mother. And he was handsome — “Eli yüzü düzgün” ("his hands and face are in order"). But there was that seemingly insurmountable barrier, he was a soldier! And surrounded by hostile neighbors, the country seemed continually on the brink of war. There was also another factor to take into account: a successful and well-heeled engineer had also asked for my mother’s hand, and a man not in constant jeopardy of being inducted into the military. The conundrum was not trivial. My mother expressed privately to my grandmother that it was the young officer that she distinctly preferred.

After my grandparents discussed the issue between themselves, they decided that my grandfather should consult his own mother, then living in Sinop. Accordingly, he wrote a letter to my great grandparents, expressing his own uncertainty. The answer, however, would not come for several weeks.

A SECOND MEETING WITH ATATÜRK

A ball was held in 1937 in Ankara at the Halk Evi with members of my father’s military company assigned to serve as guards and ushers. Among the guests would be Maresal Fevzi Çakmak, five-star general and Secretary of Defense; Ismet Inönü, Vice-President, perennial “Second Man” of Turkey, and future president; and the incomparable Kemal Atatürk himself. My father was standing near an entrance, when Atatürk entered the grand ballroom of the Halk Evi followed by his retinue comprised of Ismet Inönü, Fevzi Çakmak, and other leaders. When he saw my father, Atatürk gestured to him, appearing to have recognized him. After a short pause, he actually started walking over to my father, who immediately ran over to greet him. Atatürk asked, “Weren’t you introduced to me at commencement ceremony at the Kuleli a few years ago?” My father answered nervously that he was. “Then young man, come and sit with us at our table.”

As my father’s friends, the other young officers, all looked on in puzzled silence, my father was shown his seat — between Atatürk and Inönü. His anxiety must have been palpable. Atatürk then asked him, “Do you take raki?” (Raki is the familiar anise-flavored

liquor in the Eastern Mediterranean, variously known as “ouzo” to the Greeks and “arak” to the Arabs. The clear liquid turns translucent, milky white, when water is added. It is believed that over two thousand years ago, the powerful relative of liquor was already known in the area. According to tradition, Aristotle, the legendary philosopher and teacher of Alexander the Great, offered his pupil the drink telling him that it was “lion’s milk.”) My father had never tasted raki before, but he nodded that he did, “After all, it was Atatürk asking him.” After he gulped down one glass, a kadeh, he was immediately offered another, and another. And he was in no position to refuse.

Then as dinner was being served, Atatürk asked, “Are you married? Do you have any children?” My father, his tongue now altogether liberated by the raki, mentioned being smitten by a beautiful young woman, but that her father, an eminent physician, was reluctant to let his daughter marry a military man. He also mentioned that he was still hopeful, after all, the father had not said, “No!” The normally unflappable Atatürk became noticeably quiet; then he gestured to his yaver, his aide-de-camp, to approach. He whispered something in the man’s ear, and the man departed. All very baffling!

But just then the musicians started playing Harman Dali, a folk dance of Ankara. The dance is evocative of the Jewish folk dance, the Hava Nagila, where the participants form a chain, but in this instance the dance is performed by a group of men only. Atatürk stood up, and as if on cue, the other members of the high brass all rose. Then Atatürk turned to my father, “Kemal Bey, won’t you join us?” (the honorific "Bey" is equivalent to "Mr".) By then, my father was entirely overcome with emotion, honored to be sitting next to Atatürk at the high table, imbibing raki with his hero, and now participating in a folk dance with him and the other commanders. His friends, all lined up along the periphery of the room, watched in utter disbelief! Atatürk led the dance, holding a handkerchief in his raised right hand, and my father’s right hand with his left. My father, in turn, held onto Inönü’s right hand with his own left hand, and so on. There appeared to be a hierarchy in the chain, from Atatürk down to the lower commanders, except for my father, who was distinctly out of place, so junior in age and rank to all the rest.

After the Harman dali the men returned to the table and began to sip their coffee. Afterwards, some of the men reflexively turned their cups over, if or when a fortuneteller appeared and read their fortunes from the ground coffee deposited on the inner wall of the cup.

The foregoing represented my father’s narration during the drive down the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1967, of an incident that took place thirty years earlier, in 1937. In hearing this, I remember asking rhetorically, “Of course, you told him then that you were the son of his old friend, Ismail Hakki, didn’t you?” And, again I heard my father’s familiar refrain, “No, no, I could not bring myself to tell him. I didn’t want even the appearance of favoritism.” “Favoritism,” I said in frustration, “…it would have made him so happy to hear that you were his childhood friend’s son.”

It has now been over four decades since that memorable drive to Gallipoli (Gelibolu) when my father first narrated the story, and certainly it conformed with my mother’s recollections of subsequent year. But a sequel may exist, unhappily one that I remember hearing just once — again on that trip along the historic peninsula. In this version, right after the men drink up their coffee, Atatürk’s aide-de-camp reappears and whispers something in his boss’ ear. Atatürk acknowledges the message, but takes a few more sips before standing up. Again everyone at the table springs up in deference. But Atatürk turns to my father, and announces, “‘Buyrun,’ Come, Kemal Bey, we are going to visit the doctor!

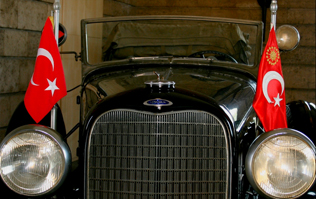

Atatürk, followed by my father and the aide-de-camp walk outside the Halk Evi, where the Presidential Lincoln sits, along with two lines of motorcycles prepared to lead the way. (Photo: Atatürk's car, 1934 Lincoln Cabriolet, Courtesy of Efser Ünsal.) With my father sitting next to Atatürk in the car, the motorcade negotiates the five or six miles to Bahçelievler, in the suburbs of Ankara. The roar of the motorcycles brings out everyone in the neighborhood. When my grandfather steps out of his house, he cannot believe his eyes. It is my father, accompanied by his “friend.” With this kind of tacit recommendation my grandfather is not about to refuse his daughter. I hope that this version is not apocryphal — a product of my own fertile imagination — but it is not outside the realm of possibility. Rather it is just that neither my grandparents nor my parents are alive now and I cannot inquire further.

Although, the last incident is one that I was unable to confirm, the following ‘sequel-to-the-sequel’ is entirely verifiable — repeated to me over the years by my mother and grandmother. Just a day before the incident at the Halk Evi, my grandfather had received the much-anticipated letter from his father (it might be remembered that my great-grandmother had been asked to counsel on the choice of suitors — “the engineer or the officer?”). This was in accordance with a traditional, perhaps centuries old practice, calling for a designated person, most likely the matriarch of the family, to go to bed, and “sleep on it,” istihare’ye yatmak. The next morning, it was hoped, she would wake up with the answer. In my great grandfather’s letter to my grandfather there was the report: “Your mother went to bed. And when she woke up she announced that she had seen in her dreams ‘… a man standing at the foot of the bed… he was wearing a uniform!’” This clinched my grandparents’ decision. Atatürk had expressed his pleasue, my great grandparents had expressed theirs. My grandparents were sanguine with their decision. My mother was happy. And my father was ecstatic! The engineer is never mentioned in family annals again.

The next time my father contacted my grandfather would be to plan the date of the wedding. It was to be in late 1938.

As it turned out, just before the wedding could take place, Atatürk passed away in Istanbul on November 10, 1938. He died in bed in Dolmabahçe Palace on the Bosporus. When one tours the Dolmabahçe now, the guides will point to the alarm clock by his bedside, poetically stopped at 9:05 am — as if by divine intervention — at the moment of his death. Although there is an apocryphal element here, there is little doubt that the collective hearts of all the Turks skipped a beat on that day. November 10th has since been recognized as the day of mourning for the ‘Father of the Turks,’ the ‘Father-Turk.’ My parents postponed their wedding for two months, finally marrying on January 8th, 1939.

In civil weddings performed in Turkey the protocol calls for the two most senior individuals in the room — sometimes celebrities, often officials or elders — to serve as the witnesses, one witness for the bride, the other for the groom. I would like to think that had Atatürk not died when he did, had my father approached him and told him about his own father, Ismail Hakki, then Atatürk perhaps would personally have been one of those witnesses at the wedding.

IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY

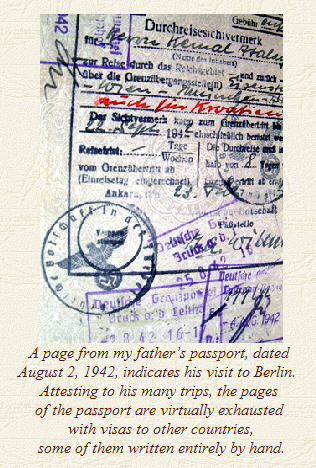

Before he died in late 1938, Atatürk had foreseen the war that was going to erupt in Europe, and had impressed on Ismet Inönü that Turkey was not to participate, but “to sit this one out!” During the years 1939-1945, my father’s tours of duty included 2-3 years as an artillery officer on a small army base west of Istanbul, overlapping with a similar period serving as courier for the Genel Kurmay Istibarat Subesi ("Office of Military Intelligence in the Defense Ministry") in Ankara. The latter tour also included two parts: a domestic component, in which he transmitted important messages received by the Minister of Defense to President Inönü, occupying the Pembe Kösk (literally the “Pink Palace,” Turkey’s White House) and a foreign component, in which he carried diplomatic pouches between the Government and its foreign embassies.

In 1939 the war indeed broke out, and the countries of Europe started being pulled in one by one. Both the Allies and the Axis Powers began to apply pressure on Turkey to join their respective sides. Churchill reminded Turkey that it had been on the wrong side of the fray during the WWI, and he made it amply clear that this time around it had better stand on the Allied side. And Hitler, for the opposition, argued the converse, “…better to side with the eventual winners.” Evidently, he had even dangled in front of Inönü the possibility that the Turkic peoples in the Soviety Union, could be integrated into a pan-Turkish nation. And yet, by 1942, Hitler had already planned an invasion of Turkey, but those plans were shelved, with Germany sidetracked by a coup that took place in Jugoslavija. In 1942, the Turkish Embassy transmitted to Ankara that it had received intelligence from the United States that the Soviets, after the war, planned to occupy all of the Balkans, as well at Turkey. The most memorable message by far that my father personally remembered carrying to President Inönü from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs came from the Americans. Roosevelt urged Turkey to remain neutral in the war. The message read, “After the war ends, Turkey is needed as a bulwark against the drive for expansion anticipated from Stalin and his Communist cohorts. We will transfer to your armed forces some of the most advanced weapons we are providing to the Allied Forces.” Turkey did indeed remain neutral. After the war, the Marshall Plan was launched, as was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), inviting Turkey as a charter member. Both of these developments bolstered Turkey’s western leaning, entirely compatible with Atatürk’s vision. Inönü, Atatürk’s always loyal right-hand man, however, was determined to follow Atatürk’s directive. Turkey would remain neutral, but with a decidedly Western leaning.

Ours was a classic extended family. My maternal grandparents owned a private house in the suburbs of Bahçelievler, but my grandfather’s medical practice was located in the Ulus Section, in downtown Ankara. Accordingly, it was there that my parents and I lived with my grandparents in a rented apartment on Anafartalar Caddesi. The apartment was commodious for those days, occupying most of the third floor of a four-story apartment building, built early in the 20th century and owned by the widow, Refiya Köklü. Across from our apartment on the third floor, my grandfather maintained his medical office, which by 1947-’48 included an x-ray machine imported from England. Just below, the second floor accommodated the Köklü Family. The ground floor featured an “ayakabici” (a shoe store) on the right side of the main entrance and a “kuyumcu” (a jewelry store) on the left. A full terrace comprised the fourth floor and offered a 360° panoramic view of the city. An acropolis, crowned by the ancient citadel, the Kale, rose prominently on the east. Isiklar Sokak, radiating perpendicular to Anafartalar, led up to the Kale, and passed a pair of institutions of special interest for me — the Archaeological Museum jam packed with Hittite relics from nearby Bogazköy and Yazilikaya, and the “Dogum Evi” (literally, “Birth House”, the Maternity Hospital) where I was born.

I remember my father occasionally going away on business trips. Too young to understand that the world was at war, I was told that his assignments in the military called for him to carry diplomatic pouches to and fro the Turkish Government and its embassies in Europe, in countries covering the full gamut of national alliances — Allied, Axis, neutral and occupied. The train on which he made his journeys, I would have thought, would have been the Orient Express made famous in Agatha Christie’s 1934 murder mystery featuring the unflappable Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot. After all, the train’s trajectory in the 1930s included some of the same capitals — Munich - Vienna - Budapest - Belgrade – Istanbul — found in my father’s passports. But it turns out that during the years 1939-1942 the Belgian-based Wagons-Lits Company, the owners of Orient Express, had suspended the train's operations. The German Mitropa company, archrivals of the Wagon-Lit, stepped in and tried running its own Orient Express into the Balkans, but principally for the transportation of military and diplomatic personnel. These routes too were suspended after 1942, with partisans waging a guerilla campaign, especially by blowing up Mitropa’s trains. These trains, however, were still available in 1941 and 1942, and it would not be far fetched to assume that father traveled to the Balkan Countries on these trains. Because of security concerns, he was instructed by his superiors in Ankara never to share a compartment with a stranger, and always to plug the keyholes of compartment doors with beeswax, lest enemy agents administer gas, in order to get their hands on the papers he was carrying.

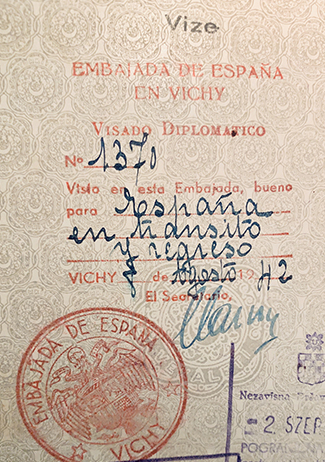

Two of my father’s surviving diplomatic passports were issued in Ankara on March 3, 1941 and July 22, 1942, respectively. Both passports, bright red in color, are comprised of 48 pages, and both specify in the two languages Turkish and French that the bearer is a “Siyasi Kuriye,” “Courrier Diplomatique” (“Diplomatic Courier”) and that the passport is valid for a single trip. The gateway for each of father’s excursions into foreign countries is Edirne, on the Turkish-Bulgarian border, although the train ride begins at Istanbul’s Sirkeci train station 210 km (130 miles) to the southeast. Ancient Roman Adrianople, Edirne is known as the site of “Selimiye Cami” (“the Mosque of Sultan Selim”) one of the defining masterpiece of Mimar Sinan, court architect of Süleyman the Magnificent in the 16th century. It must have occurred to my father at least on one of these occasions that it was here that his father, Ismail Hakki, had his only known portrait produced a quarter of a century earlier.

The 1941 passport, No. 39-118-41, is stamped with a Hungarian Visa issued on March 1, 1941 in Ankara, allowing him to make two trips into the “Magyar Kiralyi” (“Kingdom of Hungary”) before August 30. The facing page contains a visa issued on March 3rd in Ankara with permission to enter the “Kraljevine Jugoslavije” (“Kingdom of Yugoslavia”). The following pair of pages contains visas for Bulgaria and Romania. The entry and exit stamps for Hungary are dated March 11 and March 15, 1942, respectively. The 18-day trip has him leaving Turkey on March 5th and returning on March 23rd.

It is the 1942, No. 188-473-42, passport that is far more intriguing, documenting his travel all the way to the Atlantic and back. The passport, issued by the Foreign Ministry in Ankara on July 22, 1942, indicates that on the same day a visa is issued by the Royal Hungarian Legation, granting him permission to transit Hungary twice, presumably during his round trip voyage through the country. The following day another pair of visas were issued by the Romanian and by the German Chanceries. The German authorization is specific, “… permission to travel through the German ‘Reich,’ within eight days of the visa’s issue, specifically entering Germany from Eisenstadt, Austria, to travel via Vienna, Munich, Bregenz (located on Lake Constance or the Austrian part of the German Lake Bodensee). Once the center of power for the large Austro-Hungarian Empire, Austria had been reduced to a small republic after its defeat in World War I. In 1938 it was annexed by Nazi Germany. Moreover, the visa further authorizes him to pass through German occupied Croatia, Vorarlberg, Switzerland, as well as Lichtenstein. On July 24th, a hand written diplomatic visa is issued by the “Confederation Suisse” (Switzerland) that is decidedly less specific than the German visa: “…to stay ‘two or three days’ in Berne and Geneva.” The Swiss, universally known for precision, are rarely that casual with numbers. But then, individual border security officials can show a wide range of flexibility. No one is better described as the “King of his chair” than a passport control official. Frequently, it is the whims and vagaries of such individuals that can make life pleasant, or miserable for travelers… even in the 21st century.

Father's journey begins as a domestic overnight train ride at Sirkeci Train Station in Istanbul, but then becomes international as he crosses the Turkish/Bulgarian Border in Edirne on July 29, 1942. The exit stamp states, “T. C. Edirne Emniyet Müdürlügü, Hudut Emniyet Komiserligi, ‘Gittigi Görülmüstür.'” (“Republic of Turkey, Edirne Security Office, Border Security Commissioner, ‘Witness to his departure.’”) He travels through the “Independent State of Croatia” on July 31, with arrival and departure from Hungary on August 1st and 2nd, respectively. Then he enters Eisenstadt, Austria. A Swiss Passport Control official stamps his passport in St. Margareten August 4, and again on August 23, 1942 on his return, the same two days that he crosses into Germany and Austria.

HITLER'S GUN EDIT THE FOLLOWING

During his visit to Austria and Germany a year later, an extraordinary event takes place when father meets with Turkey’s wartime Ambassador to Berlin, the Honorable Saffet Arikan. From a combination of my conversations with my father during the 1970s -1990s, and a statement he wrote and signed, I could piece together the story. The Fuhrer has invited Mr. Arikan for dinner to ask him to convey to President Inönü once again why it is essential for Turkey to join the Axis Powers. Ambassador Arikan takes along a small party, including my father, to his meeting with the Fuhrer. But my father, too young (at 32) and too junior in rank, would certainly not be seated with the principals. Among those who witness the proceedings, is the Turkish naval attaché, Cpt Fahri Koruturk, later to serve as the 6th President of Turkey (1973-'80). At the conclusion of the dinner, a package is produced by one of Hitler’s aides, and presented as a gift by Hitler to the Ambassador — a mint P-38 Walther, a 9 mm pistol, Mod. HP, bearing the Serial Number 16140. It came replete with a cache of bullets and a cleaning kit. In the photograph below, the rectangular box seen in the lower left contains a cleaning cloth still in its original cellophane wrapping, and a vile of oil to lubricate the gun. After the dinner, as Ambassador Arikan departs with my father and the rest of his retinue, he turns to my father and hands over the package, “Kemal Bey, I don’t know anything about guns. I want you to have it!” And that is how Hitler’s present to the Ambassador became a present to my father and subsequently to me.

The P-38 was developed for use by German officers in WWII to replace the aging Lugar, primarily a WWI gun. Known for its legendary precision, the P-38 was still being used in the training of German officers decades after the war. In the horrific days of the war, however, it was not always regarded as a dependable weapon. Produced in factories run by slave labor, it was frequently the object of sabotage, making it as dangerous for the user as for the intended target.

Between August 7-21, 1942 Father's travels would take him to France, Spain and Portugal. The stamp at a border crossing reads, “Entering Vichy, August 15." Also appearing prominently in the passport is a visa to enter Spain granted by the “Embajada de Espana en Vichy” (“Embassy of Spain in Vichy”). The time between the defeat of France by Nazi Germany in July 1940 to her liberation by the Allied forces in September 1944 is regarded as a dark period in French history. Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain, the aging hero of France in the Battle of Verdun in WWI, is now the Head of Vichy France, the puppet government installed by the Nazis. He is on course for ignominious vilification and incarceration following WWII, just as the star of Charles de Gaulle, Head of the Resistance, is in rapid ascendancy.

August 21 father enters Switzerland at Geneva-Cornavin. He crosses the border between the Kingdom of Serbia on Sept 2 to the Independent State of Croatia, and arrives on Sept 5 in Edirne, Turkey. The 37-day Voyage from the Balkans all the way to the Atlantic Ocean and back comes to an end on September 5th in Edirne, whence he had departed on July 29th. The passport bears the stamped message, “Witness to his return.” An exceedingly devoted family man, how happy he must have been to be back in Turkey, and on his way to see his young family living in Ankara! He was blessed with a remarkable memory. During the calendar year 1993 when my mother was ill, and I made numerous trips to Istanbul, we would pull out a suitcase jam packed with photos. In seven such visits, we sorted the photos by decade, by year, by month, and on some occasions, by day. To my amazement, he could distinguish the chronological order in a pair of photos shot a few days apart. I do regret not asking about the details of those two trips as a foreign courier. Indeed, I know that there was also a visit to Moscow, which must have come in a subsequent year. More than once he recalled visiting an antique store, where he tried to purchase jewelry as a present for my mother.

During the domestic component of his assignment during 1942-'44, we lived in the tiny village of Yassiviran (since then renamed "Yassiören") in Thrace, approximately 80 km (50 miles) west of Istanbul and close to the Black Sea. Years later father told me about being awakened in the middle of the night, and rushing out with his men to help the survivors of a ship sinking off the coast in the Black Sea. Unhappily, there were only a handful of survivors, and the mission to the coast became one of retrieving bodies being washed ashore, and burying them on the beach. This had to be the wreck of the Struma on Feb 24, 1942 with Jewish refugees trying to get to Turkey, with plans to eventually get to Palestine. Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins, children of the survivors of the unspeakable calamity, wrote a poignant account in their book, Death on the Black Sea: the Untold Story of the 'Struma' and World War II's Holocaust at Sea (HarperCollins, 2004). In their book is a short passage echoing Churchill and Hitler's messages to Turkey. "The outbreak of war increased the pressure on Turkey from all sides. Its geographical setting as a land bridge between Europe and the Middle East made the country a natural haven for Jews trying to evade Nazi persecution as central Europe and the Balkans fell to the German army. The Nazis demanded that neutral Turkey not permit the immigration of Jews, and the Turks did not want do anything that would risk a Nazi invasion. Simultaneously, the British renewed their demands that Turkey halt the flow of Jews to Palestine." The mindset to provide a permanent Jewish homeland in Palestine was not even being considered seriously by the British for another five or six years, in fact, the land would be promised simultaneously to both the Arabs and the Jews.

Less than a year after the termination of hostilities, in January of 1946 my father was appointed assistant military attaché to London. Just five years old, I remember well sailing from Istanbul, by way of Izmir to Cairo; then after several weeks in Cairo, flying in a British military plane to London, with a stopover in Malta. The photograph of my father, wearing his uniform, was taken when he assumed the post in London in 1946. My sister Gülseren was born in London in 1946, but after just seven months, would be returned by my visiting grandparents to Turkey, where they would take care of her. The adjacent photo of my mother and two of her friends also married to young diplomats was taken at Buckingham Palace in 1948. (She is on the right holding her coat.) At the end of the year my father was promoted to Lt. Colonel and assigned to a new post, assistant military attaché to Paris.

After Paris, a pair of domestic assignments would follow — two years in Sivas, then an assignment in Ankara, as an assistant to the Chairman of the Joint Chief’s of Staff, Org. Nuri Yamut. These assignments would be followed in 1953, with another foreign assignment — this time to the “sweetest of all plums” among diplomatic posts. He was assigned as the military attaché to Washington, DC.

About the time that my father’s assignment to Washington expired in 1955, I was awarded the War Memorial Scholarship, and enrolled at St. Andrew’s School, in Middletown, Delaware. Founded in 1930 by the du Pont Family, this is an academically rigorous boarding school, with an unusually beautiful campus, featured in the 1989 Robin Williams movie, Dead Poets’ Societ. (Indeed, I was serving as a member of the Board of Trustees of the school when the film was made.) During the three years I spent at St. Andrew’s, and subsequently the 9-10 years I spent doing undergraduate and graduate work in theoretical physics at a variety of institutions in the United States and England, my parents were living in Turkey. My father had assignments to Malatya, then Gelibolu (Gallipoli), followed by Izmir, where he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in 1960.

During the decade of the 60s, my father had assignments to the NATO Headquarters in Izmir. Then he was based in Ankara, where he served as Commandant of the Jandarma, Undersecretary of Defense, then in Istanbul as the Commander of the First Army. In 1967, when he was receiving his final promotion, I had the singular honor of pinning a fourth star on each of his epaulets. I had missed all his other promotions through the ranks, and this would be my first and very last chance.

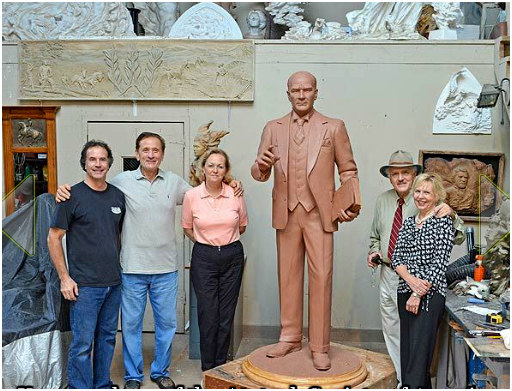

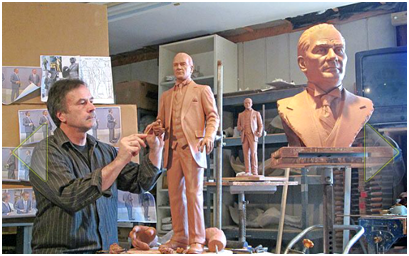

EPILOGUE — DISTINGUISHED LIVES

I have long envied the Irish who organize wakes for their dead, celebrating good lives and not just mourning for them. To be sure, we may miss immensely those departed. Leonardo da Vinci’s words, “A life well-lived is long,” resonates with meaning for both of my parents, who left remarkable memories, lived such wonderful lives. My mother died in 1993 just barely into her seventies — somewhat young for our times. She had lived an astounding life – recognized by everyone who met her for her wisdom and selflessness, her wit and humor, the elegance and astonishing beauty. When General Matthew Ridgway (1895-1993) and his wife, “Penny,” came to visit Turkey in 1952, my mother was assigned as Mrs. Ridgway’s escort during her visit. Indeed, this turned out to be a time of immense ambivalence for my mother – she was with the Ridgways in Ankara, when her beloved father passed away in Istanbul in September 1952. A year or two later, when my father was serving as the military attaché to Washington, the Ridgways came to visit us in our home — Ridgeway at the pinnacle of the armed forces of the United States, my father a colonel in the Turkish Army, and indeed they all maintained a correspondence for years afterwards. Fifteen years later when Charles de Gaule came to Ankara on a visit, my mother was assigned the seat next to the great man at the official state dinner. She exuded charisma, and she spoke French as well as English.

By any measure, my father had a long and distinguished career. Having graduated from Kuleli in 1930, he retired in Istanbul in 1970. My sister and I gave a surprise 50th wedding anniversary party for our parents on January 8, 1989, and some of their closest and oldest friends were in attendance. We showed slides (several of which have been integrated into this story). My mother died in 1993 after a prolonged and debilitating illness. At the time, I tried getting in touch with her friend, Penny Ridgway, only to find out that General Ridgway had also passed away that year, at age of ninety-eight.

My father lived a longer life than my mother — having been born nine years earlier than she was and surviving nine years past her death — died on February 14, 2003. He lived to see five of his eight great grandchildren. A grandson and a great grandson were named after him. His defining virtues had been his kindness and wisdom, his unassailable honesty and his legendary modesty; and above all his graciousness. He would never open a door, without insisting on someone else going through it ahead of him. He would never see guests to the door, and not wait outside until the guests had entered their cars and departed. He never spoke ill of anyone else. Finally, I cannot remember a day that passed when he did not mention Atatürk with deep veneration!

How appropriate it was that such a good and honest man, so full of love, would die on St. Valentine’s Day. Late in the summer of 2003, as I completed the manuscript for a book on Leonardo da Vinci that I had been writing for several years, I felt the painful ambivalence in penning the dedication, of noting the terminal year of his life.

“To the memory of an extraordinary man

— soldier, statesman, father —

General Kemal Atalay (1910-2003).”

REVISITING ISMAIL HAKKI — 1968 and 2021

Over the years, my father cited the only direct memory of his father as “no more than a dreamlike vision from his childhood.” It had taken place a few days into the New Year 1916, when he was barely five. After leaving Gallipoli in December 1915, Ismail Hakki had made his way first to Edirne, then to the town of Biga, located about 90 km (53 miles) east of Gallipoli, where his wife and children had been sheltering during the Gallipoli campaign. But, after just a brief stay in Biga, he was on the road again for his new assignment in Southeastern Anatolia. Where exactly in Southeastern Turkey, however, my father would have no idea… until 52 years later.

Two years before retiring as a military officer, in 1968 father had been visiting the southeastern cities of Malatya and Diyarbakir. The latter, situated on the banks of the Tigris River, is an ancient city featuring a well-preserved Roman Bridge and a meandering city wall second in length (albeit a very distant second) only to the Great Wall of China. The Romans had built a wall, that was subsequently expanded and fortified by the Selçuks and Ottomans. By then an “Orgeneral” (four-star general), father was in the area for an inspection of the 2nd Army troops.

One day during his stay, an elderly stranger approached him. After introducing himself, the stranger told my father that he had been following his career for decades, that he knew about his assignments, promotions, and his family. Then, to father’s astonishment, the stranger claimed he had personally known “Ismail Hakki Bey,” adding, “…I know where he is buried… in Silvan.” My father was stunned by the stranger’s claim. Although somewhat skeptical, he asked the stranger if he would take him to the cemetery, about an hour by car. There, he saw for the first time his father’s grave. Inscribed in Arapça (old Turkish) from right-to-left, the headstone read: “Chief Justice of Selanik Yusuf Ziya’s son, Deceased, Ismail Hakki, Cavalry Major, 1881-1916.” Having heard that Atatürk had been present at Ismail Hakki’s death, it was most likely that the headstone was created on Atatürk’s behest and that he was present at the interment of his friend.

After the restoration of Ismail Hakki's grave in 1968, a group of military officers had gathered to pay their respects. My father is not present in the photo, having returned to Ankara. In the upper left of the photo, a tall stone wall is visible, a clue to the grave's location along one of the boundaries of the cemetery.

For me, Yusuf Ziya suddenly stepped out into the light from the unwritten history of my family as my paternal great grandfather. I had known that my maternal great grandfather, Faik Efendi, whom I had met as a child — had been a "müftü," a justice adjudicating cases according to Islamic Law in the northern port city of Sinop. But with the revelation on the headstone, I learned that my paternal great-grandfather was also a judge adjudicating cases by secular law. The marker also identified Ismail Hakki’s brigade as based in Ohri, Macedonia, where my father was born in 1910. Macedonia had been part of the Ottoman Empire since the mid-14th century but seceded in 1912 and joined a new coalition of nations comprising Yugoslavia. In Silvan, father hired a local stonemason to restore the weathered headstone and re-inscribe the epitaph in modern Turkish with the Roman Alphabet reading from left-to-right.

2021. The Second Year of the Pandemic

Another 53 years passed before anyone in our family was able to visit Ismail Hakki's grave again. In early 2020, the Coronavirus-19, originating in China, had begun to spread rapidly around the world. In the second year of the worldwide epidemic, specifically in June 2021, my son Michael Kemal Atalay (named after his grandfather) was organizing a trip to Southern Turkey for his immediate family — his wife Elizabeth and their four offspring — Amelia (22), Alexander (20), Isabella (18), and Zachary Kemal Atalay (16), named after his great-grandfather. The grandchildren’s academic calendar and Michael’s annual break from the hospital dictated the dates for the trip: July 16-30. Approximately a third of these days would be spent in the southeast of Turkey and the other two-thirds in the southwest, all at a sprinter’s pace. Michael was able to book flights to Istanbul, and then onto Sanliurfa, along with lodgings in different cities. With crucial help from his cousin Gündüz Tansel and Gündüz's travel agent-friend Seref Aral in Istanbul, he also managed to procure ground transportation. A spacious air-conditioned Mercedes SUV that could accommodate eight passengers along with a chauffeur/guide. Here we truly lucked out. Seyfettin Karatas was an unusually gracious man who knew the area intimately. And although he demonstrated facility in Turkish and Kurdish, he spoke little English.

When Michael had first asked Carol Jean and me to join them, we had been slightly reticent. Relatives in Turkey had suggested, “Wait for the Fall when the weather will be more conducive to travel in an area famous for its Death Valley-like temperatures, 40°C-50°C (104°F-122°F). The area would be crowded, overrun by almost three million refugees from Syrian. Nine of the 14 days would coincide with the religious holiday of “Kurban Bayrami,” “…when traffic would clog the roads… animals would be slaughtered, shared, and devoured, some along the roadway.” And, the Covid-19 pandemic was still raging globally, with Southeastern Turkey identified among the hot spots for the disease. Although we were fully vaccinated, Carol Jean and I were in the high-risk category. Michael quipped, “You will have your own doctor traveling with you.” So, what did we do? Throwing all caution to the wind, we accepted the invitation, completed our PCR tests and the paperwork for the travel health visa required by the Turkish Government.

A few years earlier, while perusing FaceBook, I had come across a page “Harp Madalyasi ve Çanakkale Harbi — The Turkish War Medal & Gallipoli War,” (https://www.facebook.com/groups/harpmadalyasi/permalink/1126913960734793), administered M. Demir Erman. I had joined the group hoping to gain some information about Ismail Hakki’s final resting place. In early July, when Carol Jean and I finally decided that we would accompany Michael’s family, I posted a query on the FB site, introducing myself as a professor and expatriate Turk living in the United States. I described my grandfather Major Ismail Hakki who had been a childhood friend of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Selanik (Thessaloniki), and a fellow warrior in the Gallipoli Campaign. I explained that he had died in Silvan, and that my father the late Kemal Atalay had discovered his father’s grave and had it restored in 1968. I also posted the only photo of the grave we had in our possession, with the cadre of Turkish officers standing next to the grave and a high stonewall in the background. Finally, I queried, “Is there anyone out there who can advise us on how to even begin a search for the grave of Major Ismail Hakki?” I admitted I had no idea of how many cemeteries even existed in Silvan.

Within a few days, several responses were posted. The two most promising were from a Suat Akgül, a historian and researcher living in Antalya, and from Murat Özden Uluç, an official in the Education Ministry in Ankara. Mr. Akgül explained that he had inventoried the gravesites of WWI soldiers and compiled hundreds of photos of graves… displaying a wide range of preservation. His suggestion was to look for the grave at Kara Behlül Cemetery, its only access through the courtyard of the Kara Behlül Camii (Mosque) on Kara Behlül Sokak (Street). Murat Uluç wrote that his cousin and namesake Murat Geçmez lived in Silvan and he volunteered the cousin to pace the cemetery in a search of Ismail Hakki’s grave. The cousin obliged and sent a few photos through Mr. Uluç. The best candidate was the picture of a desecrated grave, the headstone and upper course of stone blocks missing, but located behind the grave was a wall resembling the one in the 1968 photo.

Michael’s plans had called for visiting the 12,000-year-old Neolithic temple complex in Göbeklitepe ("Potbelly Hill") near Sanliurfa and the colossal 2nd century BC statues on Mt. Nemrut. In an area of the wold where BC signaled "old" and AD "new," Mt. Nemrut was just barely old, Göbeklitepe "really old." Ancient Rome was still 10,000 years in the future! We were excited in seeing these two sites, especially after acquiring a new friend in archaeologist Ibrahim Halil Sarisu who gave us a connoisseur's tour of Göbeklitepe. On July 20, after we toured Diyarbakir, we set out for Silvan, lying 74 km (46 miles) to the east. Along the way we saw the first of many speed warnings on the highway — a full-size cutout of a police car and standing in front of it, a cutout of a police officer standing on a pedestal and holding a sign, “Slow down.” And sometimes we would see an actual police car next to the road, but with the officer sitting in his airconditioned car. It was understandable. At midday the temperature on my iPhone read a scorching 108° F (42° C).

The prospect of locating Ismail Hakki’s grave was still in the realm of a pipe dream. Sitting next to Seyfettin Bey in the car, I was doing my best to avoid appearing pessimistic that we would find the grave. When our GPS brought us to Kara Behlül Cami, we gathered our cameras and entered the mosque’s courtyard. I saw an elderly man sitting at the mosque’s entrance and asked him about the cemetery. Absorbed in his own world, he didn’t respond. But two teenagers who overheard me, led us through an unobtrusive gate across the courtyard to the cemetery. I could immediately see the same general view of the cemetery captured in one of Suat Akgül’s photos. We were in the right place! The appearance of the foreigners, all with cameras, cellphones, and especially the tall young, smiling faces, three of the four females with natural blond hair and blue eyes attracted a small crowd. When one friendly fellow asked what we were doing, I gave him a short version of our quest: seeking Ismail Hakki’s grave. He replied that he had a friend who lived across the street who might be able to help us, and immediately pulled out a cellphone and made a call to him. Meanwhile, the crowd of youngsters dispersed in different directions all looking for the grave in the photo. Within minutes, a well-groomed man with premature gray hair appeared. He was the recipient of the phone call. He was the man who lived across the street. He introduced himself as Serhat Aktan.

Left: The grave thought to belong to Ismail Hakki, badly damaged in the internecine fighting between the Turkish military and the PKK during the 1990s. The upper course of blocks and headstone were apparently removed for use in other graves in the cemetery. Because of the grade in the ground, the grave displays one more course viewed from the foot than from the head. Right, Serhat Aktan examining the grave. In the upper left is the Kara Behlül Mosque.

Serhat Bey, born on July 1, 1966, just nine days before Michael, was the “abi” (the "older brother"). Meanwhile, Seyfettin Bey returned, explaining that he had just paced the entire cemetery, grave-by-grave, and had not seen the one in the 1968-photo. As luck would have it, however, at the moment we met Serhat Bey, we were standing virtually next to the desecrated grave in the photo. Serhat Bey invited us to his home to meet his family and join them in celebrating Kurban Bayrami. We stayed for hot tea, cold drinks, and dessert, but could not take them up on a full holiday feast. We had to be on the road for our next destination, Malibadi Bridge, lying just 20 miles to the northeast, followed by a much longer drive south to Mardin. However, as Serhat Bey’s siblings arrived, we met them all and wished them a Happy Holiday. Then we took group photos. There were 15 of us. I thought I felt the frustration that they all must have felt, they could not speak with each other without my translating their words. Yet, there was communication. The women in our group were invited upstairs to visit other female relatives. An elderly woman, the boys’ mother came down, walking with a cane. She told us that she was Armenian and that her late husband had been the Belediye Baskani (Mayor) of Silvan. The hospitality and warmth of the Aktan family had helped in unifying our two families.

The Aktan and Atalay families pose for a group portrait. Standing on the far left is Serhat. His brothers Hayrettin and Medet along with Hayrettin's wife Sehnaz and son Süleyman (kneeling on the left) are also in the photo. Among the visitors are Zach and Alexander (kneeling in the center foreground), Michael (standing fourth from the left), Carol Jean (sixth from the left). Elizabeth, Amelia, and Isabella comprise the trio standing on the right.

That mutual sense of bonding became clear two months later. In late September, I received a WhatsApp message from Murat Özden Uluç in Ankara, the man who had originally shared with me the photograph of Ismail Hakki’s grave in tattered form. Attached to his message were several new photos that Murat Bey’s cousin (also Murat) had taken. In one of the photos he is standing with Serhat Aktan, behind a freshly restored grave of my grandfather. Serhat bey had taken upon himself to do additional research. He had consulted an elderly cousin who actually remembered the original grave. He located the stone of the same type and restored the grave, replete with the identifying epitaph, “...Yusuf Ziya’s son… Deceased: Cavalry Major Ismail Hakki …” Murat Uluç added, “Serhat Bey wanted to surprise you. Please, don’t tell him you already heard from me.” Several members of the extended Atalay family, those in the United States and Turkey, were overwhelmed by the grace and generosity shown by Serhat Aktan. My sister Gülseren, sheltering in her summer home in Çesme, and my cousins Nilgün and Refan in Istanbul and Izmit, repectively, all contacted him with their own messages of gratitude and offered compensation. His response was that he would not accept any. When I wrote to him of our emotional and financial debt and offered to pay for his time and expenses, he made it clear, he would not hear of it. He wrote, “As long as we are all alive, you will always be welcome in our home.” We say, “ditto! He and his family are welcome in our homes.” Ultimately, it was Ismail Hakki’s story that had brought us together.

Left. The restored grave seen from approximately the same angle as the original 1968 phto. Right. Murat Geçmez and Serhat Aktan standing behind the headstone of the restored grave.

After we left Silvan, we reached the historic Malibadi Bridge. Built 900 years ago in the time of the Selçuk Turks. Again, we poured out of the SUV and took photos from multiple vantage points. We witnessed a young couple posing for a wedding portrait with the bridge in the background. Elizabeth, Zach, and I walked up the gentle slope on the right side of the bridge, Michael and Alexander climbed down to the banks of the river. The towering arch must have been designed to allow tall ships to transit when the River Batman flowed with greater volume. The best photos of all were produced by Alexander who launched his drone to capture a bird’s eye view. The temperature on my iPhone showed 50° C (114° F).

For the finale of this story, I offer a summary from historian Suat Akgün’s communiqué regarding Ismail Hakki’s final days:

“On April 16, 1916, Atatürk and Ismail Hakki left Silvan to inspect troops. As it was getting dark, they set up tents and camped at the Malibadi Bridge. Then three weeks later, on their way back to Silvan on May 8, they set up camp in the village of Malibadi next to the bridge. Then 50 days later, Ismail Hakki, serial number P. 1312-212 ["P for Piade," or Cavalry] was dead. A graduate of the class of “1312 on the Islamic Calendar” [AD 1896 in the Common Era]. According to the official death report, he had succumbed to dysentery on June 29, 1916. His close friend Izzetin Çalislar reported that he had died of cholera. They agreed on his age. He was 35 years old.”

Malibadi Bridge photographed by Alexander's drone. The specs for the bridge follow: 250 m (480 ft) in length, 7 m (23 ft) in width, 19 m (62 ft) in height, and a main span of 38.6 m (127 ft). Although reminiscent in shape to the famous Ottoman "Mostar Bridge" in Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is half a millennium older.

My family will remain eternally grateful to Suat Akgül, Murat Özden Uluç, Murat Geçmez, our intrepid driver and guide Seyfettin Karatas, and to the entire Aktan Family — the brothers Hayrettin and Medet; Hayrettin’s wife Sehnaz and son Süleyman. However, it behooves me to single out again that especially noble soul Serhat Aktan. Though he wore no skull cap, the unassuming, gentle, pious man, we were told, was a veteran of a religious pilgrimage to Mecca. He was a devout “haci.”

ADDENDUM

The following is based on three separate blogs written for National Geographic News Watch in May 2012 by the author:

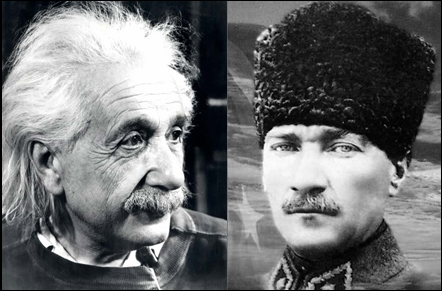

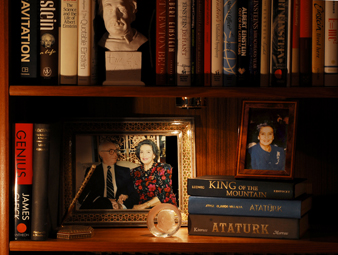

EINSTEIN AND ATATURK

This story represents the confluence of two of my lifelong heroes. First there is Albert Einstein, the greatest scientist since Isaac Newton, and Time Magazine’s choice for “The Individual of the 20th Century.” As a professor of physics for four decades I have been intimately involved with almost every component of his work — the photoelectric effect, the special and general theories of relativity, his contributions to statistical mechanics, and much more. And I have had several stints at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, walking the hallways that Einstein traipsed the last third of his life. My first stint came during the summer of 1974, 19 years after he passed away. But then I’ve known three individuals well, who knew Einstein well. I’ve already written a pair of blogs about Einstein for the National Geographic News Watch series, and in the future will write another two or three more.

Then there is Kemal Atatürk, military hero of the Gallipoli Campaign of WWI, who went on to establish the Republic of Turkey. His creation replaced a lethargic and largely illiterate Ottoman Empire, a Caliphate, at the brink of disintegration with a Western-leaning, progressive secular nation. He was driven by a dictum of “… science and reason over superstition and dogma.” In 2002, when Arnold Ludwig, a professor of psychiatry, released his book, King of the Mountain, examining the nature of political leadership, he compared and ranked all known national leaders of the 20th century. The ranking is based on the Political Greatness Scale, PGS, that Dr. Ludwig had formulated by distilling the attributes of individuals whose names have come down through the ages as synonymous with leadership — Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Charlemagne, Washington… Among the criteria are attributes such as military prowess; the nature, number and lasting power of the reforms; the length of tenure; the size of the population…. (Moreover, since one nation’s hero is frequently another nation’s scourge, Ludwig, made every attempt to filter out “the evil factor.”) On the PGS a perfect score is 37 points, but not one — including those leaders that define the standards — could possibly have scored a perfect 37. FDR and Mao Zedong, both immensely effective in changing the fabric of their nations, are tied for 2nd place among the 2000+ leaders, each with a score of 30 points. Stalin and Lenin fall immediately behind them with 29 and 28 points, respectively. Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman and Ronald Reagan also rank exceptionally high, with scores of 24, 23 and 22 points, respectively, all in the top 0.1%.

Finally, according to King of the Mountain, Atatürk, following his military victories against all odds, launched an extraordinary range of reforms. These reforms — social, legal, economic and educational in nature — completely transformed his nation. His tally, a stratospheric score of 31 points, is the single highest score among all the leaders of Ludwig’s “baker’s century,” spanning 101 years. In short, Atatürk stands alone at the summit of Ludwig’s Mountain. Sadly, eight decades after the founding of his secular Republic, the political party AKP took over in 2002 and launched a program of counter-revolution, systematically reversing Atatürk’s reforms. What the future holds is uncertain, but describing itself as “a Moderate Islamic Government,” it may well be emulating Iran, or trying to revive the old Ottoman Empire.

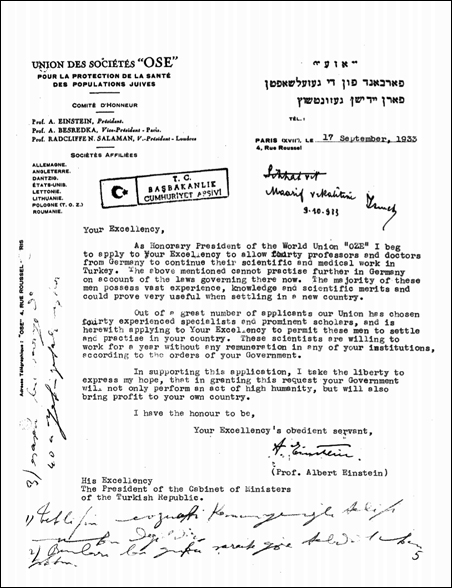

Against this backdrop, it was just 2-3 years ago that I learned about a letter that Albert Einstein had written in 1933 to Kemal Ataturk's Turkey.

THE EINSTEIN LETTER

A video prepared by Çankaya University in Ankara gives the historical background to the letter. According to the narrative (in Turkish) in 1949 Einstein meets a young foreign student, Münir Ürgür, at Princeton. When he learns that Ürgür is a student from Turkey, he shows visible excitement, “Do you know,” he says, “…your nation produced the greatest leader of the century!” Einstein then goes on to reminisce about having received an invitation from Ataturk, “… to come and teach in one of our universities. However, as fate would have it,” he continues, “…it was not to be.”

[Note. In the early 1930s Einstein, already a great celebrity physicist, was serving as a visiting scholar at Christ Church, one of the colleges of Oxford, while also trying to wade through a myriad permanent job offers. He had finally narrowed his choices down to three, Oxford, Caltech and Princeton University (Princeton, it seems, was his first choice, "... they were the first to accept relativity.”) when a brand new institution emerged to entice him. Abraham Flexner, who had made Johns Hopkins into a premier medical institution, had recently persuaded the Bamberger Family (of department store fame) to fund a new scientific 'think tank' in Princeton, New Jersey. The institution, the Institute for Advanced Study, would allow scholars to engage in research in theoretical physics and pure mathematics, to collaborate with each other, without the burden of having to teach students. Then at the Bamberger Family's insistence, Flexner had journeyed to England and convinced Einstein to join the faculty of the Institute. Einstein would be Flexner’s first faculty recruit and the nucleus around which other great scientists, many of them Eastern European Jews, could gather.]